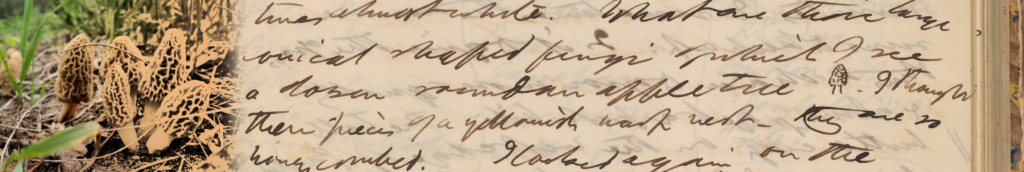

What are those large conical shaped fungi of which I see a dozen round an apple tree —I thought them pieces of a yellowish wasp nest—they are so honeycombed.

Annursnack, Sunday May 15th 1853

(MA 1302:12; Courtesy of the Morgan Pierpont Library)

Welcome to the Thoreau Drawings Archive

In a well-known essay, entomologist and paleontologist Samuel H. Scudder recalled his first encounter with Louis Agassiz, who set him the task of observing a fish preserved in alcohol. Scudder stared at the fish for some time. “At last a happy thought struck me—I would draw the fish,” he writes, “and now with surprise, I began to discover new features in the creature.” Agassiz approved: “‘That is right,’ said he, ‘a pencil is one of the best eyes.’”

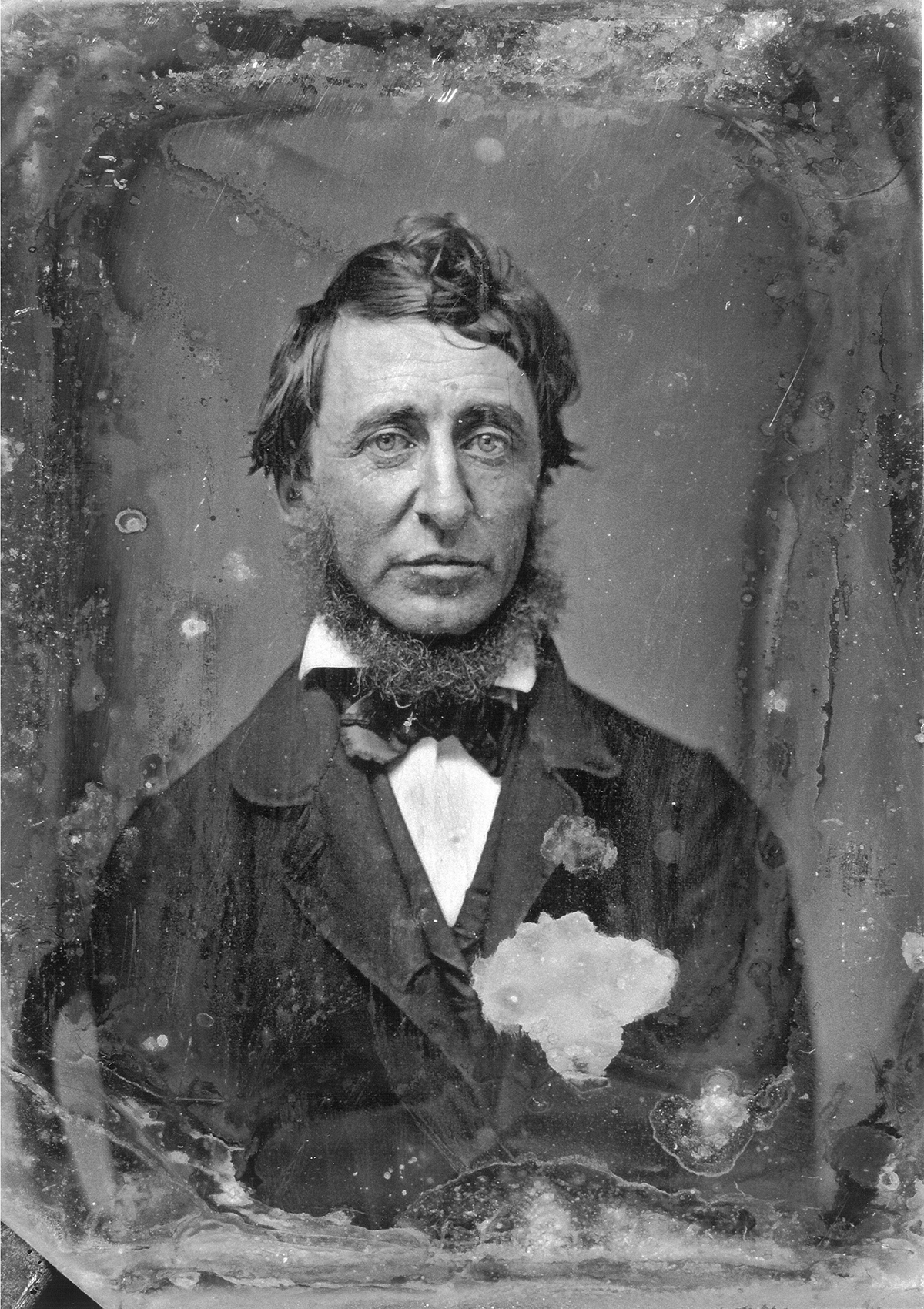

Thoreau, who may have seen Agassiz draw while hearing him lecture at Harvard, apparently came to the same conclusion thirteen years into keeping his Journal. In 1850, around the time that his interest in the natural sciences intensified, Thoreau began to incorporate drawings—a hedgehog’s quill, a locust’s wing, a goldenrod leaf, a cloud formation, the effect of wind on water—in the observations that he put in writing on his almost-daily walks around Concord.

We invite visitors to participate in the next stages of Thoreau’s Journal Drawings. The database and website are not complete, and we welcome your feedback, questions, and corrections, as well as contributions to our collection of projects based on the Journal drawings.

We invite visitors to participate in the next stages of Thoreau’s Journal Drawings. The database and website are not complete, and we welcome your feedback, questions, and corrections, as well as contributions to our collection of projects based on the Journal drawings.

Early on in Walden, Thoreau tells us that he borrowed an axe from a neighbor, remarking: “It is difficult to begin without borrowing, but perhaps it is the most generous course thus to permit your fellow-men [and women] to have an interest in your enterprise.” We hope readers will lend their expertise and enthusiasm, and promise to return Thoreau’s Journal Drawings to them sharper than when we began it. Contact us at HDTdrawings@northeastern.edu.

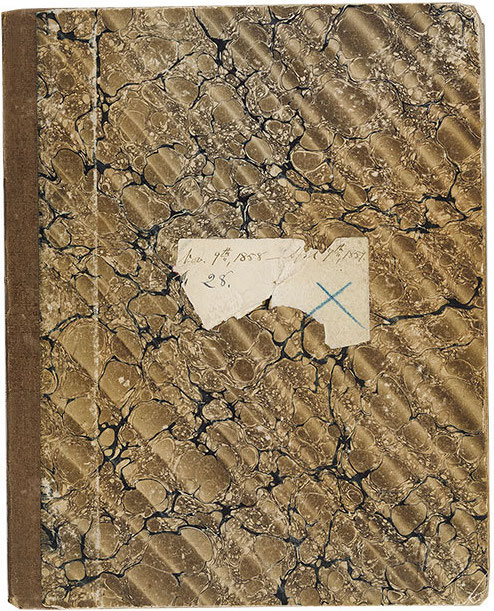

Cover of Journal, MS Volume XXVIII, 9 November 1858–7 April 1859 (MA 1302; courtesy of Morgan Pierpoint Library)

The archive invites visitors to study the variety and scope of Thoreau’s drawings on their own merits as well as to examine the interplay and interrelatedness of texts and image in the Journal. Attending to the drawings enhances our understanding of Thoreau’s methodology and growth as a natural scientist committed to observing, describing, and representing the natural world. The search feature allows visitors to survey the Journal drawings using dates and keywords.

This site offers an opportunity to pose a number of questions, not only about the drawings themselves, but also about their wider social, intellectual, and cultural context: what did Thoreau choose to draw—and how did he draw? What can we discover about the nature and quality of the drawings? (Some are quite compelling; others are mere schema.) What do the drawings say, by themselves and for themselves? Is it possible to discern changes in style over time? Changes in interests? What was the nineteenth-century art-historical and historical context for such drawings? What happens when we place Thoreau’s drawings in the context of eighteenth and nineteenth-century theories about how one ought to produce scientific illustration?

Finally, the drawings ask that we return to Thoreau’s manuscript itself. Examining how Thoreau placed his drawings in relation to the text on the page can be quite revealing. Moreover, spending time with the manuscript prompts us to consider the many contexts in which we have encountered Thoreau’s Journal. The Journal, in whole and in part, has been presented to us across a variety of media and through various, often quite specialized, viewpoints. This database is yet another example: one reads for drawings as one might read the Journal selectively for Thoreau the ornithologist, say, or the philosopher, or the abolitionist. How has such a profusion of versions and iterations influenced how we read, appreciate, and interpret the Journal?