Site Overview

The Journal

Selected Images from Thoreau's Journal

Hen Hawk: “The tail-coverts of the young hen hawk . . . are white very handsomely barred or watered with dark brown in an irregular manner somewhat as above—the bars on opposite sides of the midrib—alternating in an agreeable manner” 11 November 1858 (Volume XXV; NNPM MA 1302.31) (courtesy of the Morgan Library, and as featured on the Library exhibits page, "This Ever New Self: Thoreau and His Journal")

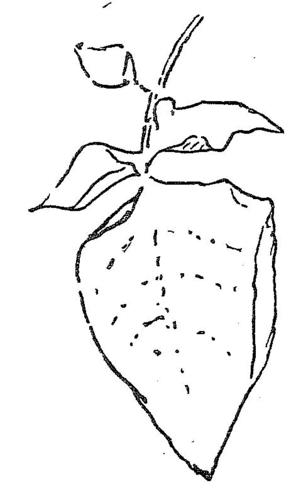

Leaf Crystal: “On the ice at Walden are very beautiful great leaf crystals” 1 January 1856 (Volume XIX; NNPM MA 1302.25) [detail] (courtesy of the Morgan Library)

Getting it right: Thoreau crosses out his first drawing of the leaf-like ice, and is more careful the second time around. (The blue canceling line is H.G.O. Blake’s.) (courtesy of the Morgan Library)

Remarkable Moth:“I found a remarkable moth lying flat on the still water as if asleep” 8 July 1852 (Volume XI; NNPM MA 1302.17) [detail] (courtesy of the Morgan Library)It is impossible to capture in a printed edition how words and drawings sometimes become entangled in the Journal. Which came first—text or moth?

Weasel or Mink: “we saw a mink a slender black . . . very like a weasel in form” 2 December 1852 (Volume XII; NNPM MA 1302.18) [detail] (courtesy of the Morgan Library)

The Drawings

It is remarkable how suggestive the slightest drawing as a memento of things seen. For a few years past I have been accustomed to make a rude sketch in my journal of plants, ice, and various natural phenomena, and though the fullest accompanying description may fail to recall my experience, these rude outline drawings do not fail to carry me back to that time and scene. It is as if I saw the same thing again, and I may attempt to describe it in words if I choose.(10 December 1856)

![Hen Hawk “The tail-coverts of the young hen hawk . . . are white very handsomely barred or watered with dark brown in an irregular manner somewhat as above—the bars on opposite sides of the midrib—alternating in an agreeable manner” 11 November 1858 (Volume XXV; NNPM MA 1302.31) (courtesy of the Morgan Library, and as featured on the Library exhibits page, “This Ever New Self: Thoreau and His Journal” [https://www.themorgan.org/exhibitions/thoreau])](https://thoreaudrawings.northeastern.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/6-Journal-open-to-Nov-11-1-300x263.jpg)

![Leaf Drawing “On the ice at Walden are very beautiful great leaf crystals” 1 January 1856 (Volume XIX; NNPM MA 1302.25) [detail] (courtesy of the Morgan Library)

Getting it right: Thoreau crosses out his first drawing of the leaf-like ice, and is more careful the second time around. (The blue canceling line is H.G.O. Blake’s.) (courtesy of the Morgan Library)](https://thoreaudrawings.northeastern.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/IMG_0211-1856_01_01-crossed-out-drawing-leaf-crystals-detail-copy-1-300x224.jpg)

![Remarkable Moth “I found a remarkable moth lying flat on the still water as if asleep” 8 July 1852 (Volume XI; NNPM MA 1302.17)

[detail] (courtesy of the Morgan Library)

It is impossible to capture in a printed edition how words and drawings sometimes become entangled in the Journal. Which came first—text or moth?](https://thoreaudrawings.northeastern.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/moth-1-300x224.jpg)

![Weasel or Mink “we saw a mink a slender black . . . very like a weasel in form” 2 December 1852 (Volume XII; NNPM MA 1302.18) [detail] (courtesy of the Morgan Library)](https://thoreaudrawings.northeastern.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/IMG_0284-weasel-or-mink-copy-1.jpg)